Held at the Comic Art Museum in Brussels on 10–11 June 2025, the BiodivClim Final Events brought together researchers, policymakers, and stakeholders to mark the conclusion of the BiodivClim CoFund Action. Launched under Horizon 2020, the initiative addressed pressing challenges at the biodiversity–climate nexus.

The first part of the events focused on the BiodivClim Knowledge Hub (KH), marking the culmination of two years of collaborative work on the biodiversity–climate nexus. Funded under BiodivClim, the KH connected 32 experts across disciplines and ecosystems to advance nature-based solutions (NbS) for climate adaptation and mitigation. As the KH concludes in August 2025, it leaves behind a valuable legacy of shared tools, new networks, and practical insights.

The second part of the event featured project presentations and panel discussions. Key themes included feedback loops, challenges of integrating biodiversity into climate models, and the importance of context-specific, long-term approaches to NbS. Participants emphasised the need for sustained stakeholder engagement, stronger science-policy links, and regional collaboration to overcome institutional silos. While trade-offs between ecological and economic goals remain, many saw opportunities for long-term synergies.

The event also featured the launch of the BiodivClim comics. Building on their successful NBS Comics series, The Nature of Cities Europe was invited by Biodiversa+ to create a new collection inspired by BiodivClim project outcomes. Three core themes—agriculture, oceans, and forests—were identified, and stories were developed in collaboration with artist teams selected by Biodiversa+.

The final part of the event was a closed foresight workshop aimed to identify future research priorities for biodiversity and climate change, with the goal of fostering coordinated European funding action. Its three main objectives were to review the BiodivClim Action, report on IPBES knowledge gaps addressed by funded projects, and contribute to a future research agenda.

Highlights

Opening the session, Karin Zaunberger from the European Commission (DG Environment) stressed the need for transformative change as ecosystems edge toward critical tipping points. She positioned the BiodivClim initiative as a frontrunner in integrating biodiversity and climate science, supporting global goals such as the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework and the Paris Agreement.

Ron Winkler, Co-Chair of Biodiversa+, presented the KH as a space for synthesising project results, identifying knowledge gaps, and enhancing science-policy-society interfaces.

KH Co-Chairs Rita Sousa-Silva (MixForChange) and Pedro Pinho (BiNatUr) unveiled two major outcomes soon to be published. The first is a research paper identifying 27 knowledge gaps on NbS and climate adaptation, later grouped into six key research avenues. The second explores barriers to implementing NbS across different contexts. Rita Sousa-Silva also highlighted the KH’s contributions beyond academia, from European Commission briefings to active participation in forums such as the World Biodiversity Forum and the recent IPBES-IPCC joint workshop.

Testimonials from members including Pelin Acar (Acorn) and Sonja Gantioler (JUSTNature) showcased the KH’s impact on national dialogues and new collaborations, noting the value of engaging a wide range of voices, from early-career researchers to high school students.

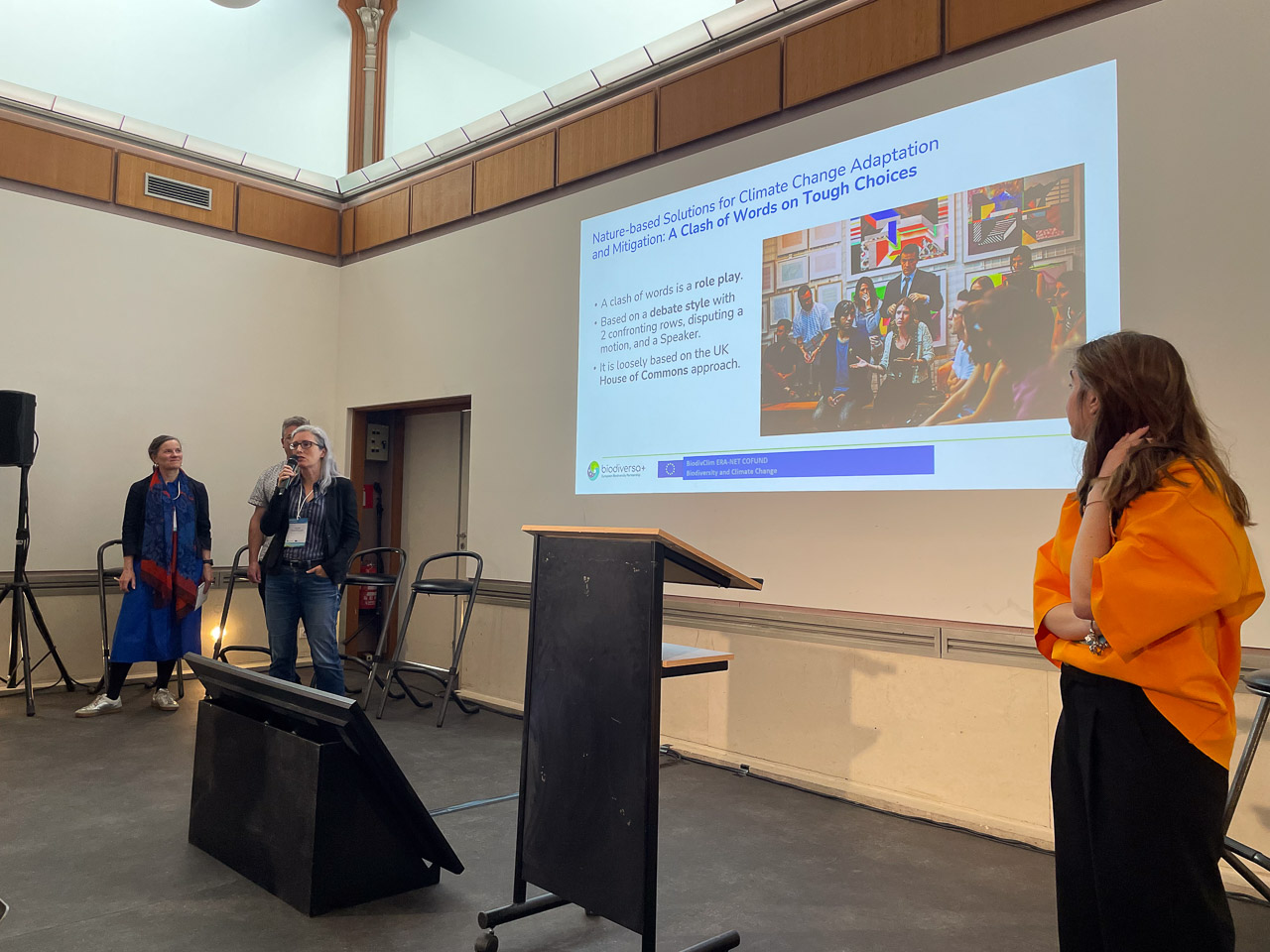

A “House of Commons” role-play session brought participants into debate, addressing tensions in NbS implementation. Participants discussed trade-offs between ecological and economic metrics, small- versus large-scale initiatives, and the roles of regulation versus incentives. While positions varied, there was broad agreement on the importance of ecological impact, context-sensitive approaches, and strong policy frameworks to enable systemic change. The session highlighted the need for shared understanding and collaboration across sectors and governance levels.

The day concluded with a closed workshop for KH members to reflect on achievements, challenges, and lessons learned. Participants valued the collaborative spirit, engaged leadership, and in-person exchanges that built trust and momentum. Key challenges included time constraints, an overly ambitious initial workplan, and inconsistent communication with key stakeholders. During the session, participants co-developed practical recommendations for future Knowledge Hubs, focusing on the need for clearer governance, better alignment between goals and resources, and strategies for sustained engagement. These insights will feed into a final KH report to be released later this year.

Feedbacks highlighted biodiversity’s overlooked influence on climate. The team developed a unified workflow to model how land-use changes and species traits (e.g., evapotranspiration, reflectance) affect climate, finding significant differences in climate-regulating traits between habitats. Their “climate insurance hypothesis” suggested that diverse ecosystems are more resilient to climate extremes, with certain land-use changes potentially causing substantial warming.

GenClim investigated the evolutionary and socioeconomic consequences of shifting marine fish populations due to climate change. Focusing on hakes and anchovies, they found varying population resilience, with implications for fisheries policy and socioeconomic stability. They stressed that a lack of population-level data risks over/underestimating future abundance and increasing overexploitation of unregulated stocks.

GRADCATCH examined how climate change affects soil microbial communities across gradients. They found that while climate indirectly influences soil functions, soil characteristics directly drive them. Fungal diversity, more than bacterial richness, was crucial for soil multifunctionality. Microbes in extreme environments showed smaller, efficient genomes. A new R package was developed for classifying microbial strategies from genome sequencing data.

FutureArcticLives focused on climate and biodiversity impacts on Arctic primary resource users. In Greenland, they quantified high reliance on hunting and fishing. For Sámi reindeer herders, “green energy” infrastructure (25% pasture reduction) posed a greater threat than climate change itself, with herders more concerned about predators and land-use changes than direct climate impacts.

The panel discussion explored cross-cutting themes: climate–biodiversity feedbacks, stakeholder engagement, and communication. They defined feedbacks as reciprocal influences, including socioeconomic cascades. Sustaining stakeholder engagement over long research cycles was a key concern, with solutions including communication officers and recognising co-creation’s time intensity. For complex science communication, they recommended interdisciplinary teams, storytelling, and simplifying messages without distortion. They also noted difficulties in integrating biodiversity into climate models due to data scarcity, computational challenges, and overlooked soil biodiversity.

ACORN addressed forest adaptation to climate change, focusing on drought-related genetic adaptation in oaks. Research across Europe revealed genetic differentiation between and within species, with adaptation occurring across geographical scales. The project advocated for assisted gene flow and using “marginal sites” for seed sourcing.

BIOFAIR studied wheat agroecosystems’ climate resilience using advanced facilities. Milder winters impaired wheat development and root systems, increasing drought sensitivity. Reduced tillage improved soil health but not consistently yield or nutritional quality. The project stressed breeding strategies aligned with short-term climate projections and emphasised systemic approaches valuing crop performance and other ecosystem services.

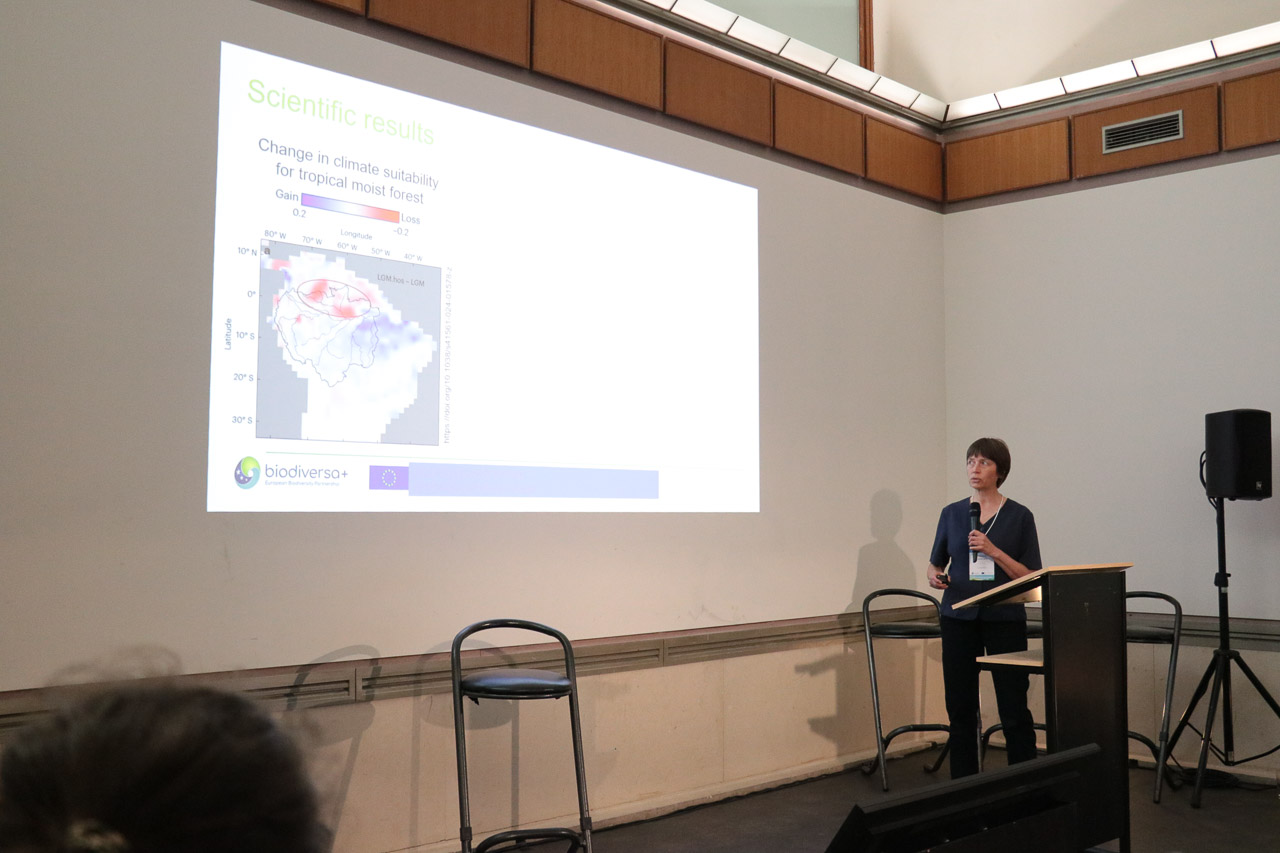

CLAMBIO explored Amazonian biodiversity and AMOC slowdown impacts on rainforests. They studied floodplain bird and fern adaptations, and assessed severe ecological/social effects of the Xingu River hydroelectric dam, which disrupted natural flood pulses. The project argued for addressing direct human impacts (deforestation, mining) alongside global climate change.

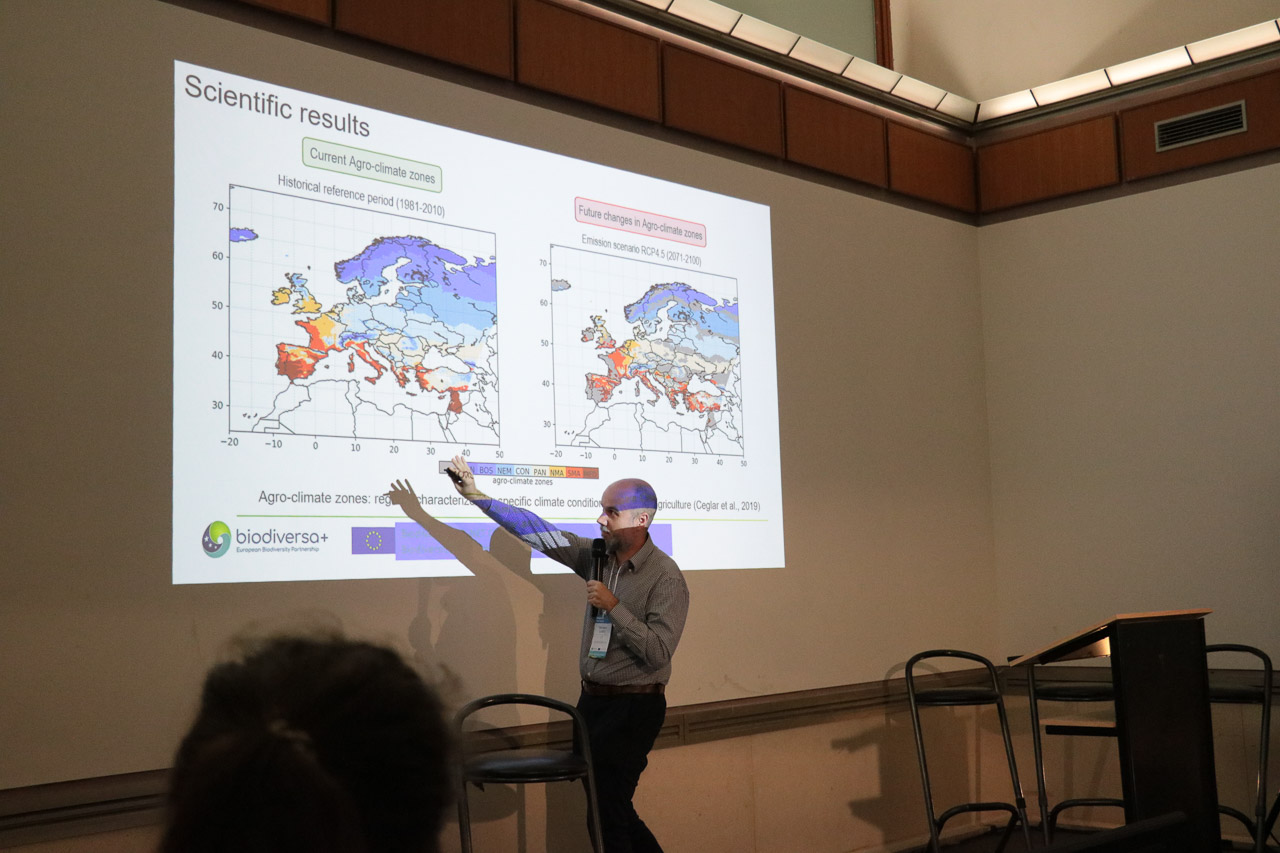

MICROSERVICES aimed to predict future soil biodiversity and ecosystem services in Europe. By defining agroclimatic zones and using machine learning, they forecast changes in soil functionality. Findings showed low-emission scenarios support higher soil multifunctionality, suggesting current investments in soil health enhance future resilience. However, sustainable practices’ buffering effects were acknowledged as complex and context-dependent.

PlantCline examined how climate change influences wild strawberry evolution across Europe. They found extensive trait diversity and clear local adaptation, especially for northern and southern genotypes. Northern genotypes showed plastic flowering phenology. The project underscored conserving valuable genetic material in common plant species for crop resilience.

RangeX focused on plant range expansion in mountains and its biodiversity implications. Experiments showed many lowland species could establish at higher elevations, but faced dispersal limitation or resistance from resident competitors. Global datasets revealed rapid upward shifts in species’ elevational limits, contributing to biotic homogenisation, particularly along road corridors.

Panellists discussed managing resource use while sustaining biodiversity and carbon goals. They emphasised locally tailored approaches and farmer incentives for sustainable practices. Direct human impacts like deforestation must be addressed alongside climate change, acknowledging trade-offs (e.g., improved soil health may increase CO₂ emissions). For policymakers, recommendations included integrating trait and genetic diversity in conservation policies, closing regulatory gaps in seed transfer, and using clear, accessible terminology to bridge the science–policy divide.

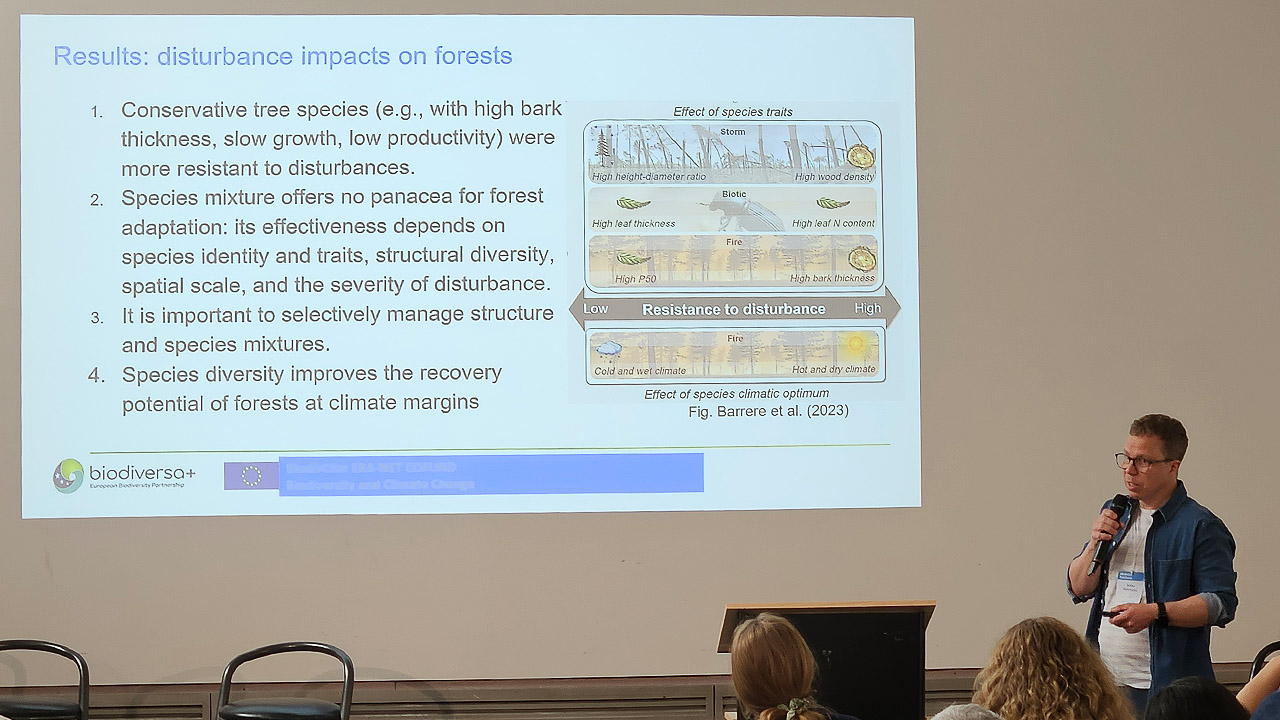

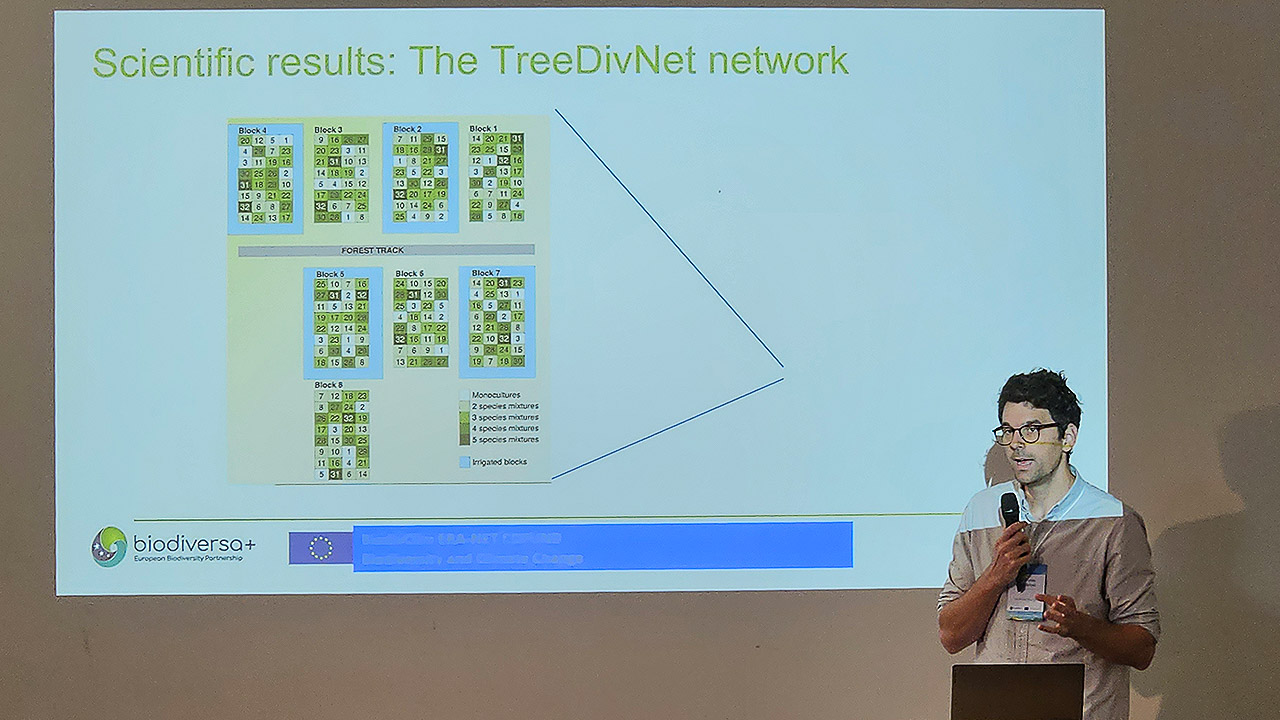

MixForChange investigated mixed forest plantations as NbS for climate mitigation/adaptation. Tree diversity, including functional diversity, generally promoted productivity and carbon storage. For drought resilience, species identity and functional traits were key. Barriers to adoption included management complexity and higher costs, while motivations were biodiversity conservation and climate resilience.

RESTORE evaluated NbS for improved reforestation, assessing drought stress on plants and soil microbiomes. Roots were seen as drought stress buffers, while the rhizosphere microbiome showed adaptive responses. The project identified promising microbial inoculants and nature-based materials (e.g., nanoparticles from agricultural waste) that improved seedling growth and drought resistance.

ASICS studied cold environments (mountains, poles) threatened by climate change and invasive species. The project focused on altitudinal shifts in plants/invertebrates, examining how changing temperatures affect their phenology, physiology, and reproductive success. ASICS developed frameworks for invasion timelines and provided conservation guidelines for protected area managers and biodiversity monitoring programs.

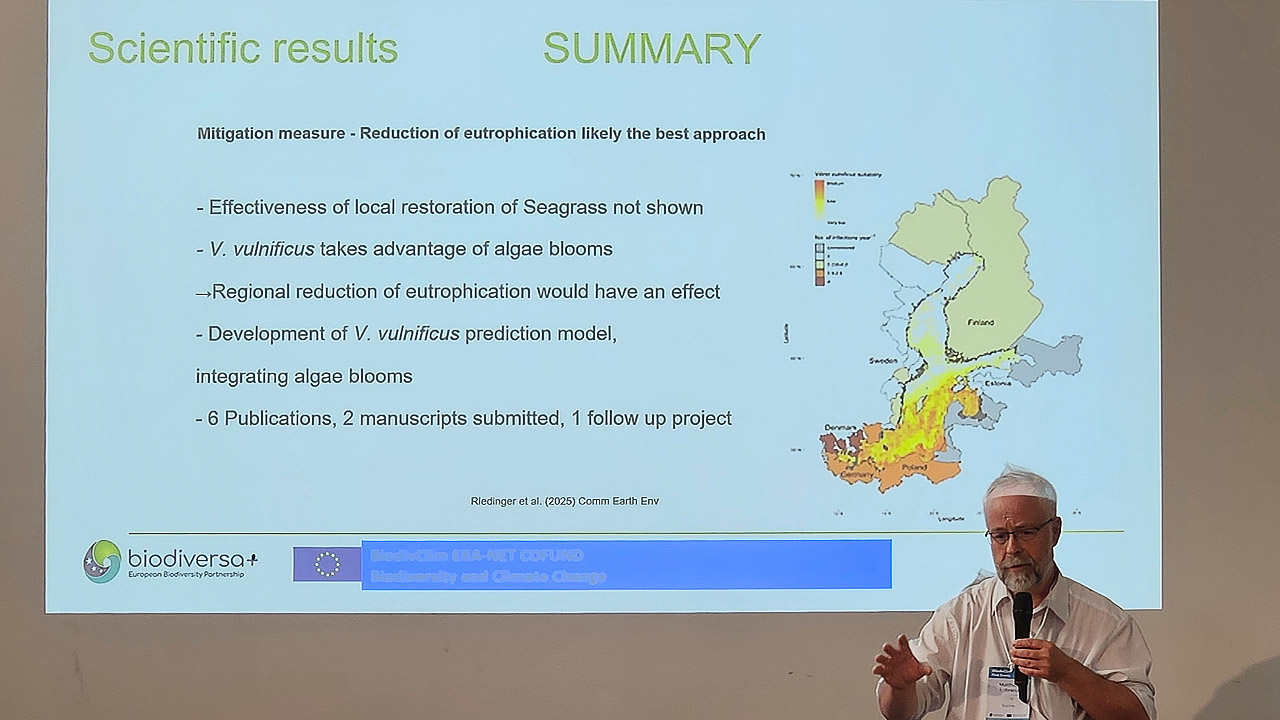

BAltVib focused on Vibrio bacteria in the Baltic Sea, a pathogenic bacterium thriving in brackish, warm conditions. Eelgrass meadows had no impact on Vibrio abundance; instead, eutrophication (decaying algal blooms) was the main driver. This highlighted that reducing nutrient input, not local habitat restoration, is key for Vibrio control in this specific context, emphasising the context-specificity of NbS.

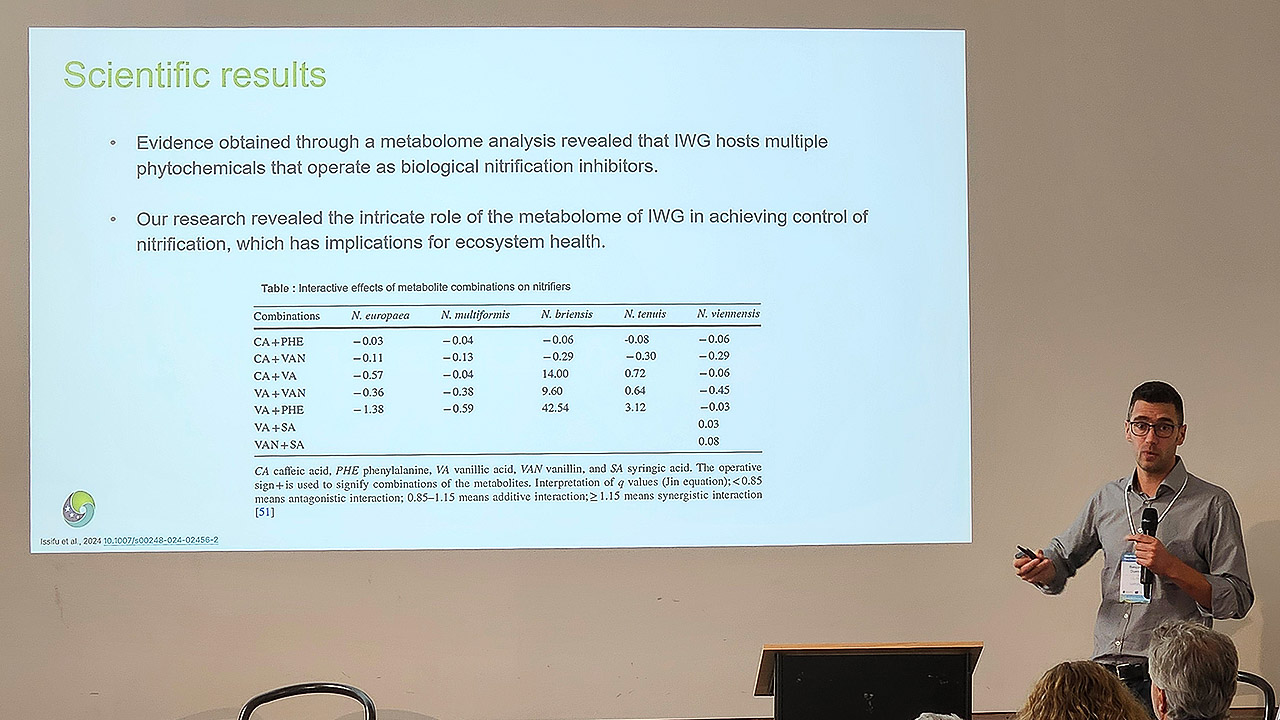

NAPERDIV explored perennial grain crops as agroecological NbS. Intermediate wheatgrass fostered richer, more diversified earthworm communities and a stable, connected microbial network. The microbiome contributed to biological nitrification inhibition, reducing N₂O emissions and improving resource use. Despite regulatory hurdles, perennial grains show promise for more sustainable and resilient food systems.

NordSalt focused on Nordic coastal marshes, studying climate impacts and biodiversity interactions. They found moderate carbon stocks but low sequestration rates, stressing the need to account for livestock and greenhouse gases. Grazing significantly influenced biomass and ecosystem services like sediment stability. Stakeholder engagement revealed high interest in biodiversity over climate.

The panel discussion highlighted key challenges in implementing NbS, including future-proofing, communication, and bridging policy gaps. While models and tree diversity were supported, long-term climate projection reliability was questioned. Panellists stressed continuous, independent stakeholder engagement, supported by professional communicators and a humble, listening approach. NbS were seen as context-dependent, offering trade-offs between biodiversity and ecosystem function. Bridging institutional silos may require systemic change (e.g., in food systems) and demand-driven research networks. Coordination, they noted, often hinges on public concern or financial incentives.

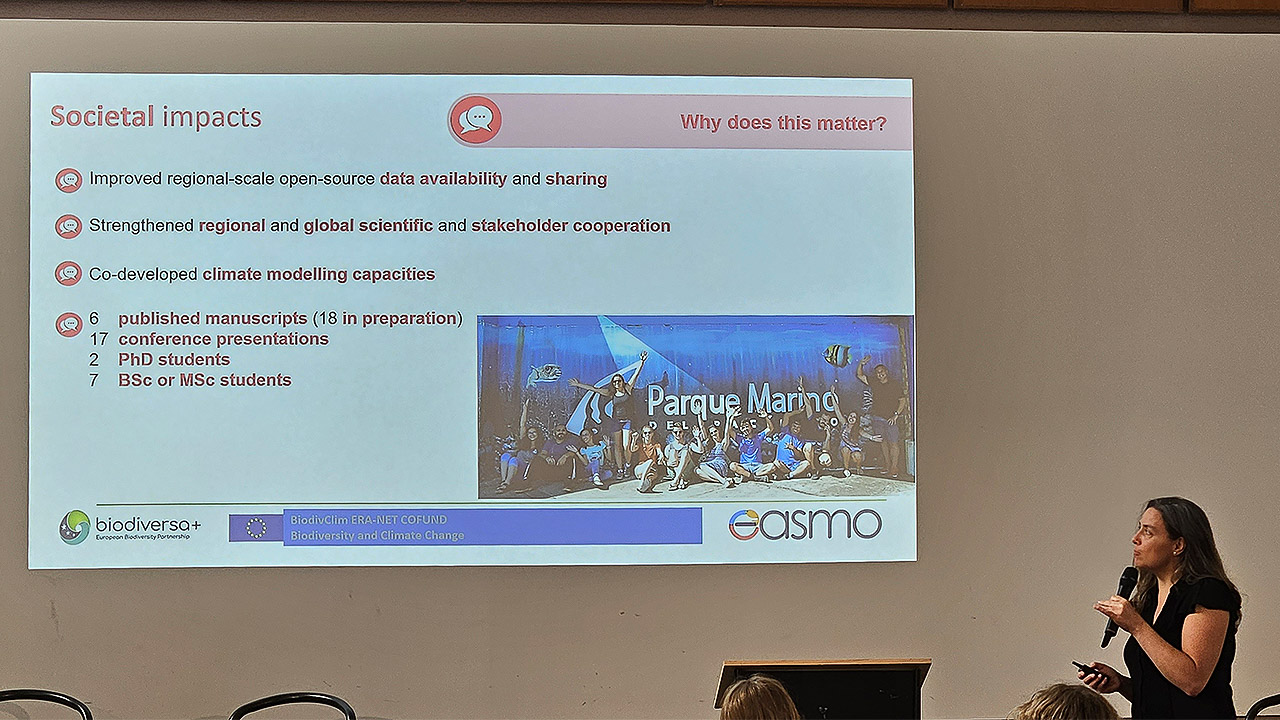

EASMO investigated coral/rocky reefs in the Eastern Tropical Pacific. Projected warming/deoxygenation by 2050 will redistribute fish, affecting their carbon cycle role and nutritional value, exacerbating challenges for fishers. EASMO advocated for region-wide coordination for mobile species management, highlighting a win-win between reef biodiversity and human nutrition, but also a potential trade-off between functional diversity preservation and food affordability.

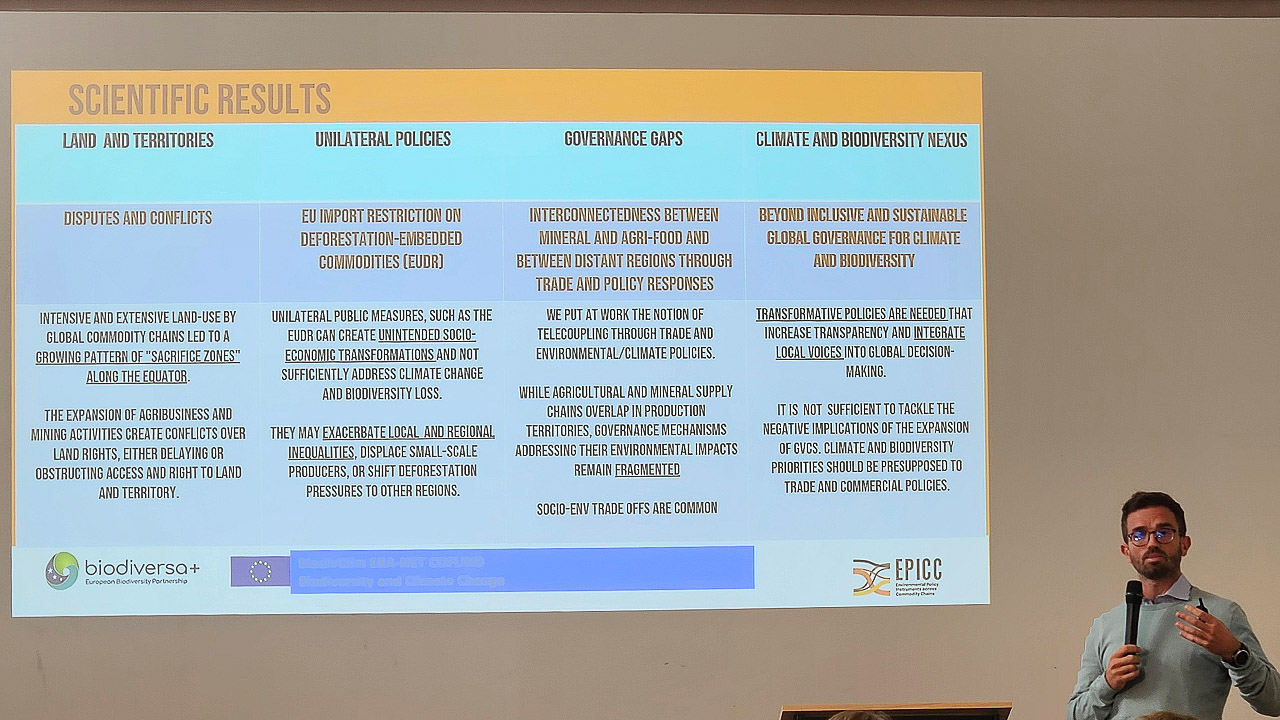

EPICC analysed global commodity chains link deforestation and biodiversity loss in producer countries to EU consumption. It highlighted the risks of policies like the EUDR reinforcing disconnects between production and consumption by overlooking the lived realities of local communities. EPICC’s core approach focused on one-on-one engagement with policymakers to ensure local realities were reflected in policy.

FUNPOTENTIAL explored how forest diversification affects resilience and profitability. Mixed-species forestry is not a universal solution but requires selective management. While stability management often trades off with short-term profit, high carbon payments could incentivise diversification. Key recommendations include harmonised national forest inventory data and policies to reduce landowner investment risks for diversification.

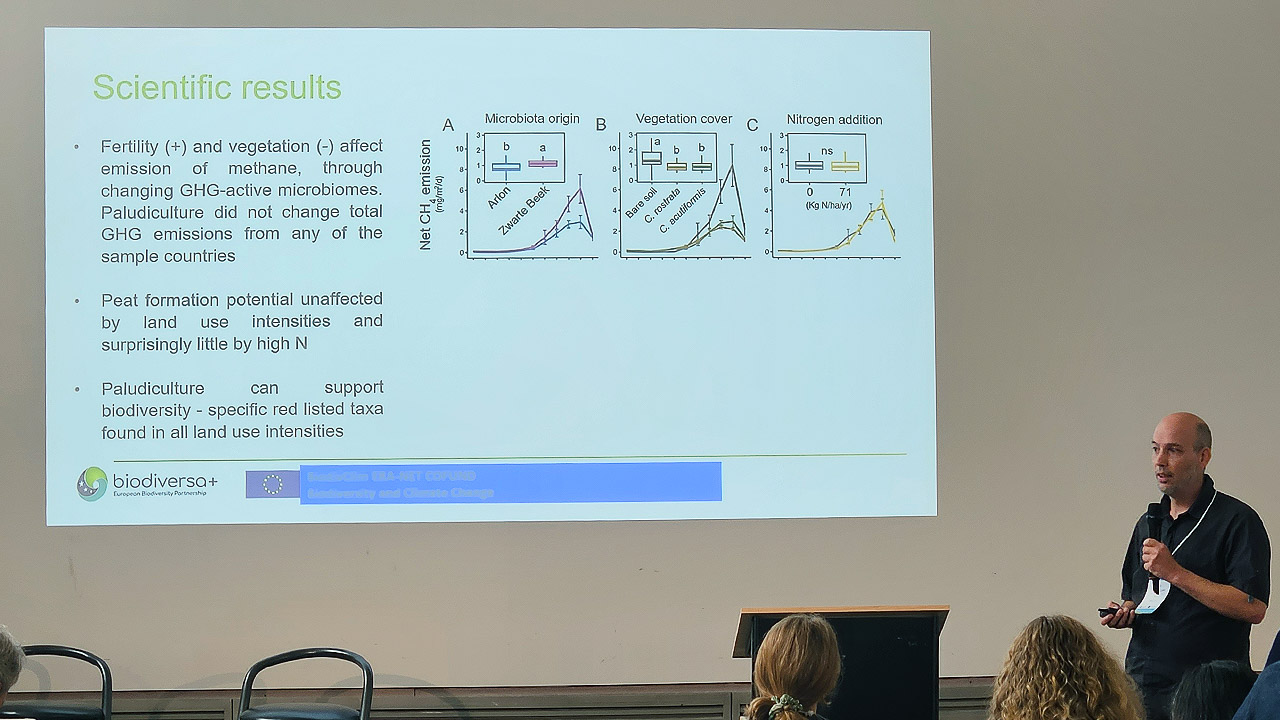

PRINCESS investigated peatland rewetting as an NbS to mitigate greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, nitrogen pollution, and biodiversity loss. Degraded peatlands are significant contributors. Experiments showed specific microbial communities and vegetation reduced methane, and paludiculture could increase biodiversity without increasing total GHG emissions. The project mapped high-emission peatlands and advocated for large-scale policy instruments combined with local agreement and economic viability demonstrations.

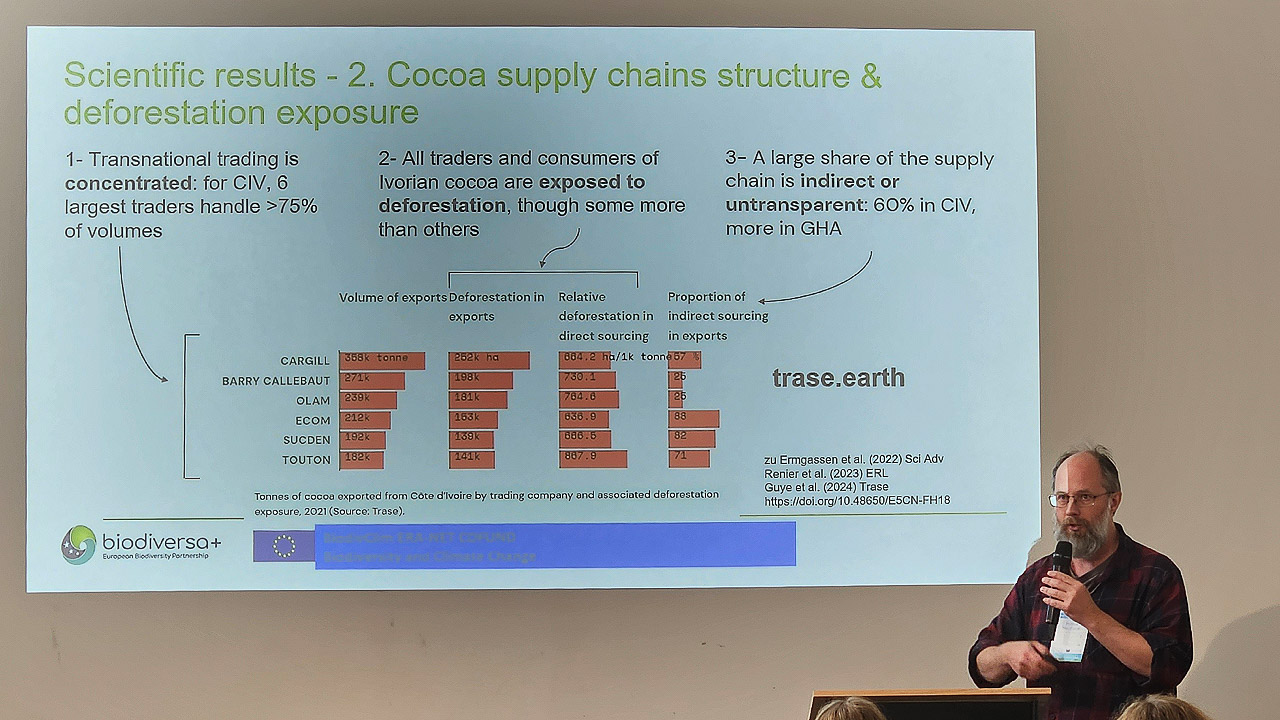

SUSTAIN-COCOA examined the West African cocoa sector, identifying it as a major driver of deforestation, with most cocoa untraceable due to informal traders. Agroforestry in degraded cocoa farms emerged as a synergy for carbon storage/biodiversity. While acknowledging short-term economic/environmental trade-offs, the project suggested these become long-term synergies. It advocated for clear mitigation hierarchy in policies, prioritising existing forest conservation.

Panellists reviewed strategies for policy impact, including building trust through direct engagement, adapting messages for broad audiences, and early involvement of policymakers. Definitions of “synergy” and “trade-off” are subjective, but biodiversity underpins multiple goals. Long-term benefits often outweigh short-term conflicts. Challenges include time constraints, limited data, underfunded communication, and barriers to decision-maker access. Recommendations included better access to EU institutions, strategic dissemination post-project, clearer trade-off communication, stronger advocacy, and fostering global collaborations.

Participants first reviewed how projects addressed knowledge gaps, particularly those identified in IPBES assessments. Working in thematic groups, they examined gaps in data, processes, and policy, and reflected on how the concept of the biodiversity–climate “nexus” was applied.

Some takeaways:

- Some gaps were seen as too broad or unfamiliar, making them difficult to address.

- Data remains a major challenge. Some projects generated new data, but access and long-term storage are still issues.

- Projects contributed to understanding adaptation (e.g., in marine systems) and the impacts of interventions and policy.

- Nexus thinking was applied unevenly and often without explicit terminology.

- Calls were made for better data management, more shared databases, and attention to persistent gaps like adaptation, functional diversity, and long-term experiments.

Next, participants explored how to advance biodiversity–climate research, through four rounds of discussion focused on emerging issues, integration, governance, and policy impact.

Some takeaways:

- Emerging issues: AI’s energy demand, political instability, pandemics, and extreme events were flagged. Equity and indigenous knowledge also emerged as priorities.

- Barriers to integration: Disciplinary silos, fragmented funding (e.g., separate Horizon Europe clusters), and short-term trade-offs hamper holistic work.

- Governance and finance: Participants called for long-term, cross-border funding, reduced bureaucracy, and more effective enforcement and incentives. Data harmonisation and integration of biodiversity-climate risks in finance were also key.

- Policy impact: The technical language of IPBES/IPCC limits accessibility. Concerns were raised about author diversity, institutional recognition, and lack of support for policy engagement. Stronger science-policy bridges and more inclusive processes were recommended.

The workshop’s insights will inform a more detailed report planned for August 2025 and contribute to IPBES information sharing.

Mark your calendars for 10-11 June 2025, at the Comic Art Museum in Brussels, as we celebrate the culmination of the BiodivClim CoFund Action!

Launched in 2019 under Horizon 2020, BiodivClim supported 21 projects exploring the crucial link between biodiversity and climate change, advancing knowledge on:

✅ The consequences of climate change on biodiversity

✅ Climate-biodiversity feedback processes

✅ The potential of Nature-based Solutions (NbS) for climate change adaptation and mitigation

✅ Synergies and trade-offs across policies and sectors

This final conference will showcase the results of these projects and mark the closure of the BiodivClim Knowledge Hub, a community of experts focusing on the potential of NbS for mitigating and adapting to climate change.

Join online!

While in-person attendance is limited, key sessions will be accessible online:

- 10 June (morning): BiodivClim Knowledge Hub final conference

- 10 June (afternoon): BiodivClim funded projects final conference, Part 1

- 11 June (morning): BiodivClim funded projects final conference, Part 2

More from Biodiversa+ in Brussels

Several exclusive in-person sessions will also take place:

- 10 June (afternoon): Knowledge Hub experts workshop (invitation only)

- 10 June (evening): Networking cocktail and presentation of comics developed from research projects, translating findings into engaging storytelling!

- 11 June (afternoon): BiodivClim funded projects foresight workshop (invitation only)

For more details, please contact Lison Cowez and Cloé Durieux.

10 June 2025

10:00 – 12:30 BiodivClim Knowledge Hub conference

- Welcome words, by Ron Winkler (BiodivClim coordinator)

- Introductory speech on the biodiversity-climate nexus, by Karin Zaunberger (European Commission DG Environment)

- Knowledge Hub achievements, by Pedro Pinho (Knowledge Hub co-chair, BiNatUr) & Rita Sousa-Silva (Knowledge Hub co-chair, MixForChange)

- Added-value for researchers, by Pelin Acar (ACORN) & Sonja Gantioler (JUSTNature)

- Interactive session on NbS [available only for onsite participants], by Sonja Gantioler, Amy Oen (EVOKED), Rita Sousa-Silva, & Tom Wild (CONEXUS)

Lunch break

14:00 – 15:20 BiodivClim funded projects’ final conference (session 1)

- Theme: Climate-biodiversity feedback processes

- Projects: Feedbacks, FuturArticLives, GRADCATCH, GenClim

Break

15:40 – 17:20 BiodivClim funded projects’ final conference (session 2)

- Theme: Consequences of climate change on biodiversity and nature’s contributions to people

- Projects: ACORN, BioFAIR, CLAMBIO, MicroServices, PlantCline, Range X

17:20 – 17:30 Presentation of the BiodivClim comics, by David Maddox (The Nature of Cities)

11 June 2025

09:00 – 10:35 BiodivClim funded projects’ final conference (session 3)

- Theme: Potential of nature-based solutions for mitigating and adapting to climate change

- Projects: MixForChange, NAPERDIV, RESTORE, NordSalt, ASICS, BAltVib

Break

11:05 – 12:30 BiodivClim funded projects’ final conference (session 4)

- Theme: Synergies and trade-offs between policies on biodiversity, climate and other relevant sectors, and the role of agents of change

- Projects: SUSTAIN-COCOA, EPICC, PRINCESS, FunPotential, EASMO

12:30 – 12:45 Conclusion