“Guide on best practices sharing biodiversity data for private companies”

Published: January 2026 | DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.16967457

Companies are collecting growing volumes of biodiversity data through environmental impact assessments, monitoring programmes, certification schemes, and sustainability reporting. Yet most of this data remains siloed, underused, or inaccessible. This represents a missed opportunity. When shared responsibly, biodiversity data can strengthen scientific knowledge, support public monitoring, and increase the credibility and effectiveness of corporate biodiversity action.

This guide provides a practical roadmap for moving from isolated data collection to meaningful data sharing, while addressing common legal, technical, and organisational concerns. It includes:

- Clear profiles of companies that generate biodiversity data

- An overview of standards, formats, and data platforms

- Real-world case studies (including TotalEnergies, Holcim, Barilla, and Biotope)

- A step-by-step roadmap for responsible and effective data sharing

Why share data?

Data sharing is not a technical afterthought. It can be a proactive corporate strategy that supports transparency, credibility, and long-term value.

Enhance credibility & transparency

Prepare for regulations

Contribute to global knowledge

Where do you fit?

Companies generate and manage biodiversity data in very different ways. Understanding your profile helps clarify what to share, how to share it, and with whom.

What’s your profile?

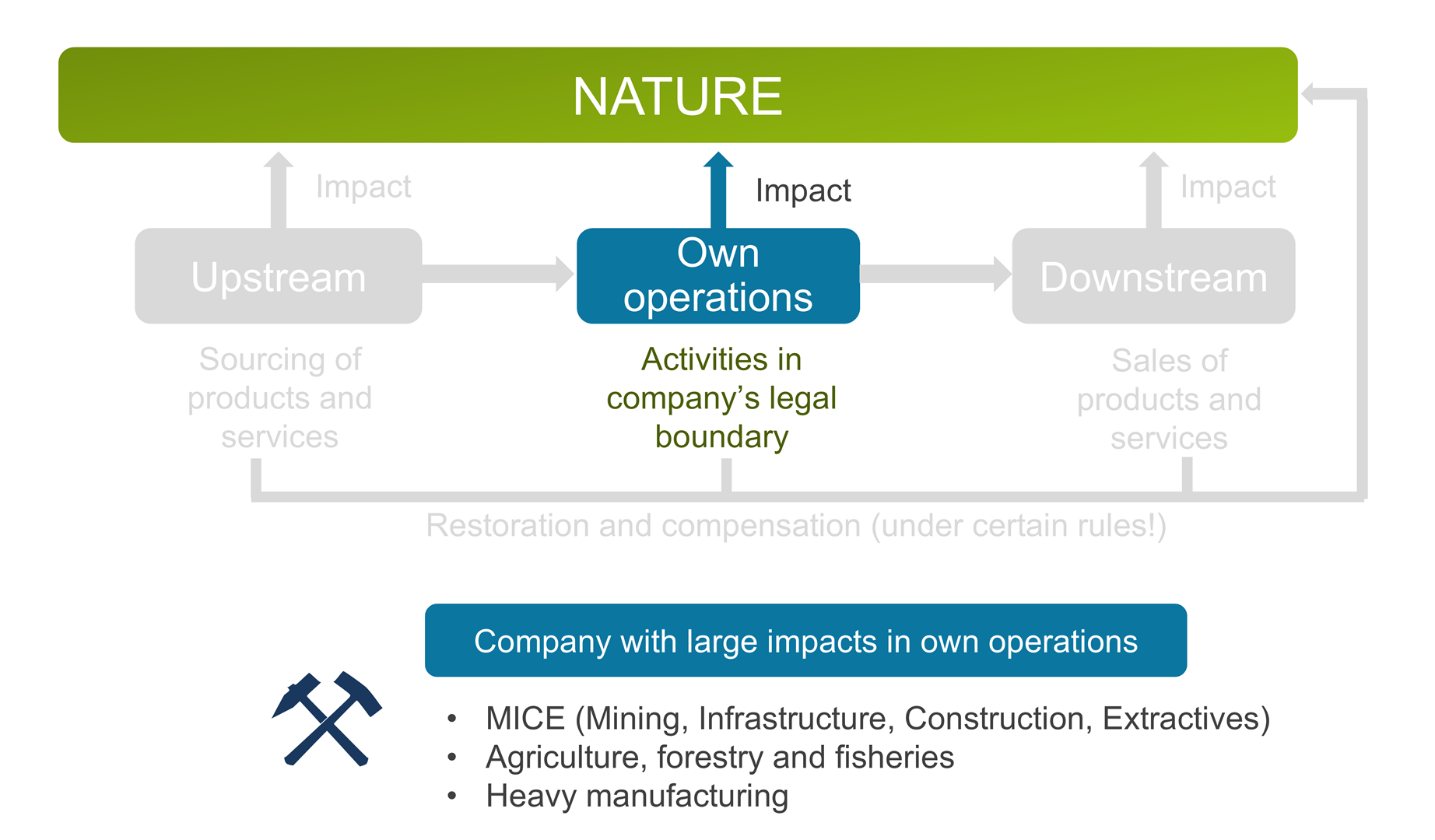

You are managing primary impact data. Operating in sectors like mining, infrastructure, construction, or primary production, your activities have localised, intensive impacts. You generate high-quality, site-specific primary data through Environmental Impact Assessments, Appropriate Assessments, and standards like the Equator Principles and ICMM guidelines.

| Most common challenges | …and solutions |

|---|---|

| Sensitive species data: Sharing precise location data risks illegal collection or exploitation. | Use approximate geolocation or obfuscation methods. Platforms often provide access controls for highly sensitive data. |

| Data ownership conflicts: Consultants or local governments may claim legal rights over collected data. | Incorporate data-sharing clauses in contracts and agreements with enablers or local authorities. |

| Data processing costs & internal buy-in: Formatting and processing data can be costly; initially seen as low-reward. | Integrate data sharing into corporate nature strategies. Develop low-cost tools to streamline collection and improve quality over time. |

Your Environmental Impact Assessment is a scientific asset. By strategically using obfuscation and standardisation, you turn compliance costs into measurable scientific impact.

How has TotalEnergies worked through this?

TotalEnergies, a global energy company, initially saw data sharing as a “low effort – low reward” task. By approaching challenges strategically, they turned regulatory compliance data into a valuable resource for science:

- Addressing sensitive data: Sharing precise locations of sensitive species posed a risk of illegal collection. TotalEnergies found that approximate geolocation was sufficient for most academic purposes, safeguarding sensitive information while enabling reuse.

- Resolving ownership conflicts: Where enablers or local governments had potential legal claims over collected data, the company incorporated counterparty data-sharing agreements into standard contracts.

- Gaining internal buy-in: Demonstrating the high value of these data to academia, where collection would otherwise be costly, helped position sharing as a concrete, measurable, and low-cost action within their broader nature strategy.

Outcome: TotalEnergies’ data has since been cited in over 270 scientific publications.

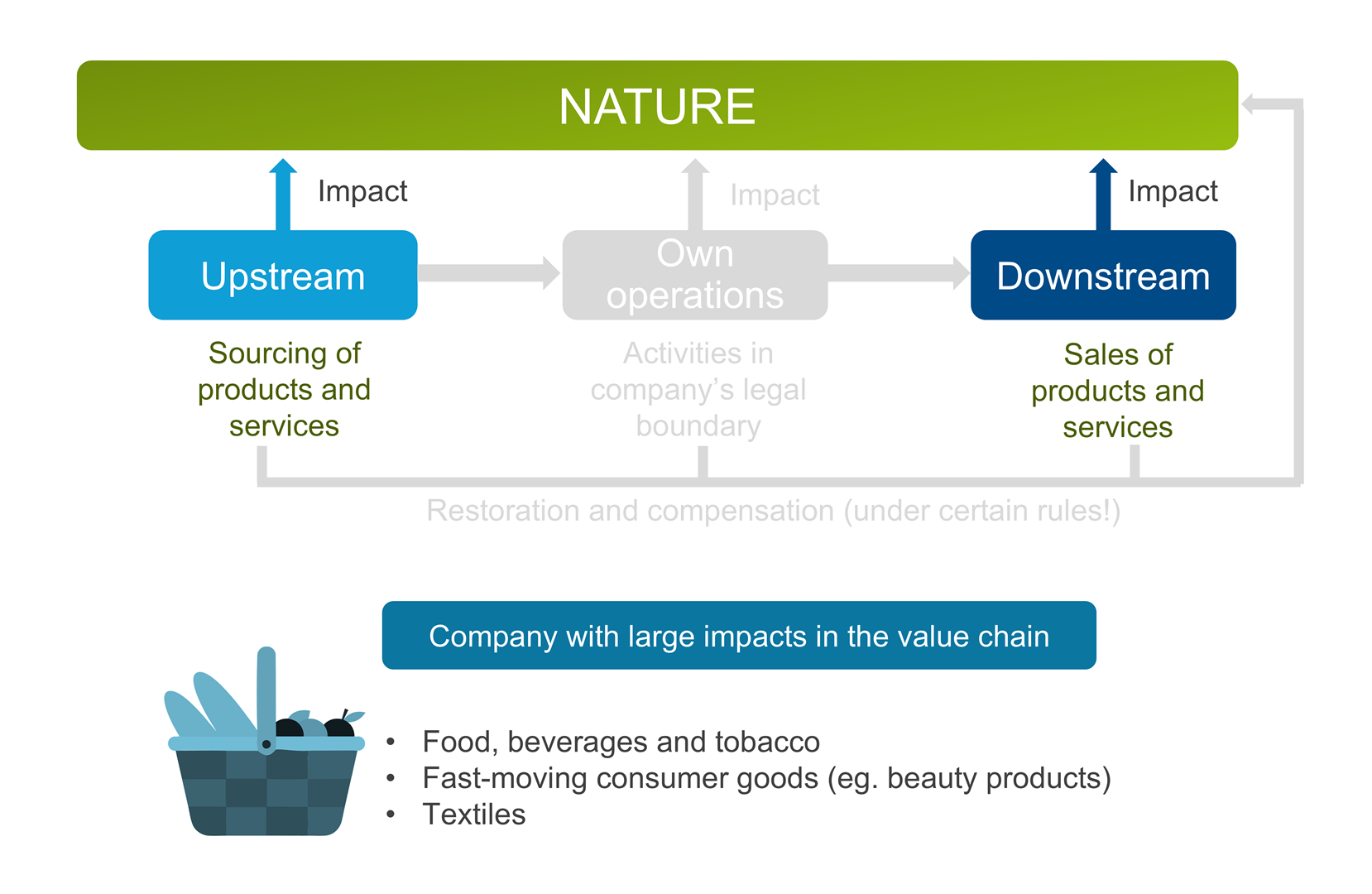

You are relying on secondary data to assess upstream impacts. As a company in food, textiles, or consumer goods, your biodiversity footprint lies deep in your supply chain. You often use secondary data for risk screening, guided by frameworks like CSRD, TNFD, and SBTN. While primary data is less common, it may be required for certain ecolabels.

| Most common challenges | …and solutions |

|---|---|

| Data ownership, collection, and scalability: Suppliers retain data, making sharing difficult. | Digital platforms (e.g., Barilla Farming App) allow voluntary supplier data sharing, easing collection and monitoring. |

| Complexity of biodiversity measurement: Indicators are hard to establish across a supply chain. | Partner with scientific experts (e.g., universities, NGOs) to ensure robust and credible measurement methods. |

| Data retention by auditors / lack of common metrics: Auditors often retain certification data; standards differ. | Negotiate data access with auditors and participate in working groups to harmonize metrics for biodiversity monitoring. |

Decentralised impact requires centralised trust. Leverage digital tools and expert partnerships to transform supplier-owned data into validated, scalable insights that future-proof your regulatory compliance.

How has Barilla worked through this?

Barilla, a major food company with 1,000-2,500 farms in its supply chain, faced challenges related to supplier data ownership and collection at scale:

- Developing digital platforms: The Barilla Farming App allows farmers to manage activities and share data voluntarily, facilitating scalable and manageable data collection.

- Ensuring credibility: Collaborations with the University of Bologna and WWF provided scientific guidance, ensuring biodiversity indicators were robust and validated.

- Gaining access to certified data: Where auditors retained ownership of certification data, Barilla negotiated access to key information to support reporting and compliance.

Outcome: These strategies enabled Barilla to monitor biodiversity impacts across its supply chain while respecting supplier rights and ensuring scientific credibility.

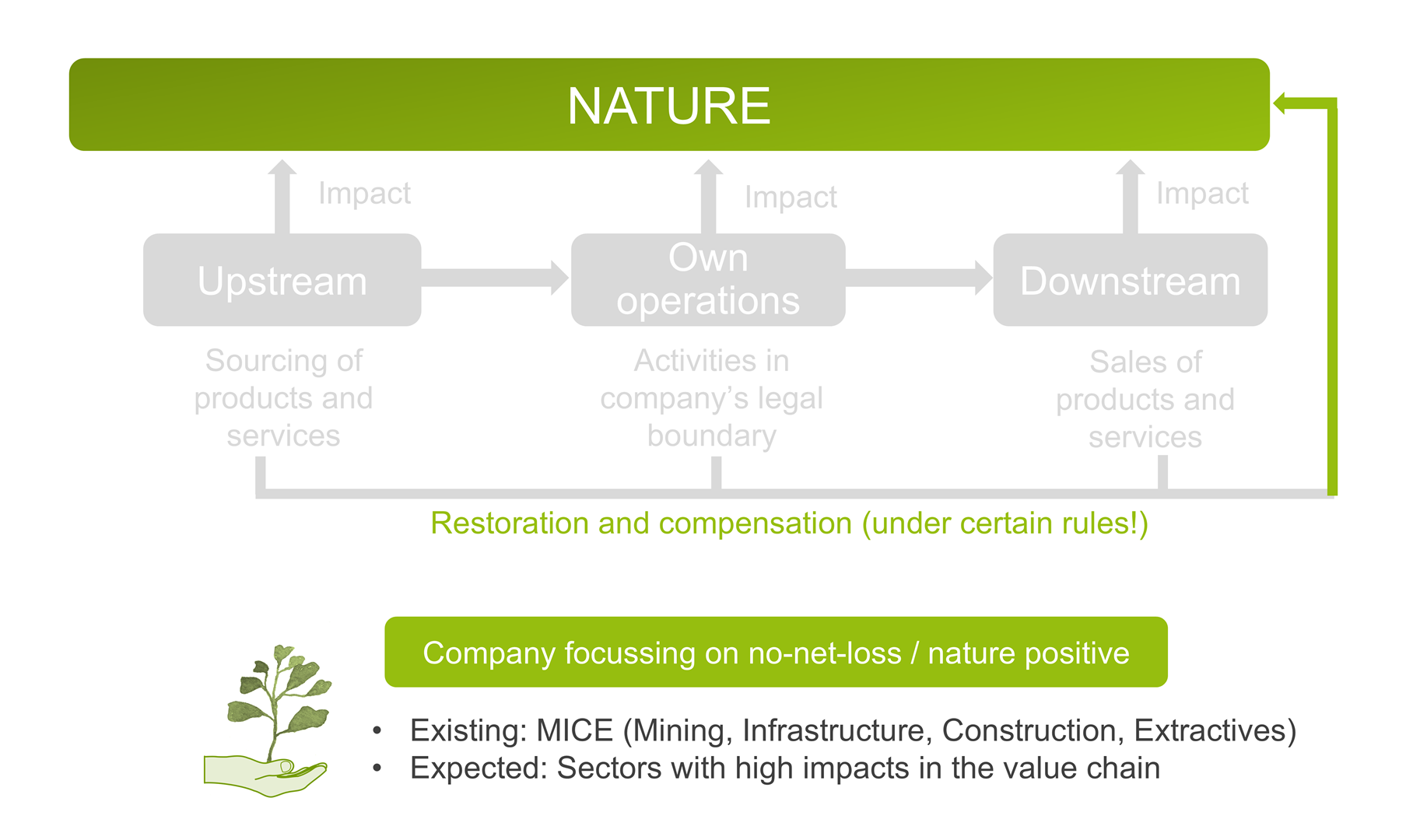

You are documenting net gains for nature. You commit to “no-net-loss” or “nature-positive” goals, often through restoration or biodiversity credit schemes. These initiatives require primary data to quantify outcomes, using metrics aligned with standards like IFC Performance Standard 6 and Essential Biodiversity Variables.

| Most common challenges | ..and solutions |

|---|---|

| Data collection expertise: Specialized knowledge is often required. | Collaborate with external experts to guide accurate, relevant data collection and sharing. |

| Initial platform difficulties: Uploading data to platforms like GBIF can be complex. | Use training and support from platform representatives. Digitize legacy datasets for streamlined submissions. |

| Lack of standardization (biodiversity credits): Multiple standards hinder comparability. | Share data via platforms like GBIF, OBIS, or national databases to improve consistency and transparency. |

Your restoration data are credible assets. Prioritise external scientific collaboration and platform training to ensure your primary data contributions accelerate global conservation monitoring.

How has Holcim worked through this?

Holcim, a multinational building materials company committed to measurable positive impacts by 2030, tackled challenges in data collection and standardisation:

- Bridging expertise gaps: Collaborating with external experts helped Holcim ensure biodiversity data were accurate, relevant, and collected to high standards.

- Simplifying publication: Training and support from GBIF representatives streamlined the process of uploading data, making future submissions faster and more efficient.

- Enhancing comparability: To address inconsistencies in biodiversity credit standards, Holcim encouraged data sharing through platforms such as GBIF, OBIS, and national databases, promoting consistency and transparency.

Outcome: Holcim strengthened both internal monitoring and external reporting, enhancing credibility for its “nature-positive” commitments.

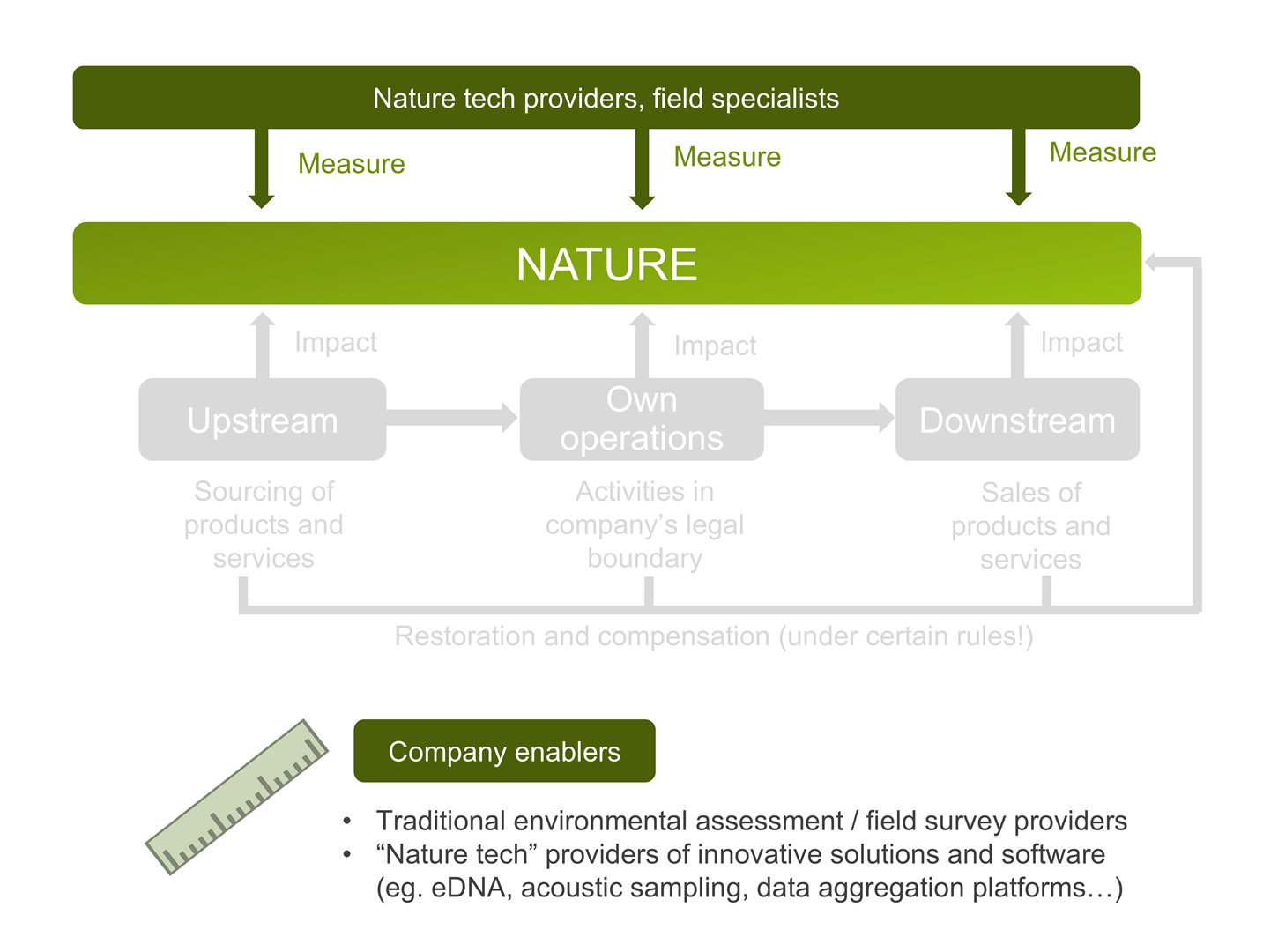

You are standardising and delivering biodiversity data services. As an environmental consultant or nature tech provider, you collect and process biodiversity data for clients. Using tools like eDNA and acoustic monitoring, you support regulatory compliance and sustainability reporting. You are among the largest private contributors to GBIF.

| Most common challenges | …and solutions |

|---|---|

| Data ownership and client agreements: Sharing requires client permission. | Educate clients on legal and ethical implications. Develop protocols for sensitive species. |

| Complex stakeholder involvement: Stakeholders may lack biodiversity knowledge. | Offer workshops and training to ensure all parties understand data-sharing importance. |

| Sensitive data handling: Endangered species data requires anonymization. | Use geolocation obfuscation and species identification protocols to protect sensitive data. |

| Technical and resource constraints: Integrating internal databases with platforms can be complex. | Develop direct API links for automated publication. Implement software ensuring consistent data collection. |

Position data sharing as a value-add service. Proactive client education and API integration are essential to transform proprietary datasets into shared public knowledge while respecting sensitive data constraints.

How has Biotope worked through this?

Biotope, a French biodiversity consultancy, often acts as an intermediary, collecting and processing data for clients:

- Managing client permissions: Biotope educates clients about the legal and ethical importance of data publication, ensuring all stakeholders understand why sharing is valuable.

- Streamlining technical workflows: By creating direct links between internal databases and external platforms, Biotope automates publication while enforcing consistent data collection protocols.

- Handling sensitive data: Protocols for identifying sensitive species and geolocation obfuscation safeguard vulnerable data while enabling controlled sharing.

Outcome: Biotope enables clients to contribute valuable biodiversity data safely and efficiently, bridging gaps between private sector operations and public scientific use.

Your 7-step action plan

Across sectors, companies face recurring barriers: unclear ownership, sensitive data, fragmented platforms, limited capacity, and lack of trust. The guide proposes a 7-step process to overcome these challenges:

Before you share anything, clarify why your company is doing it and who will use the data. This strategic first step will guide your entire process.

- Identify objectives: Are you aiming for regulatory compliance (e.g., CSRD), supporting a conservation partnership, or enhancing brand reputation? Your goal determines what data is relevant.

- Map your audience: Potential users could be scientists, regulators, community groups, or even your own customers. Understanding their needs helps you tailor the data you share.

- Engage internal teams early: Involve your sustainability, legal, and IT departments from the start to ensure alignment and build co-ownership of the process.

Outcome: Data sharing becomes a proactive corporate strategy, not a reactive technical chore, with stronger internal buy-in and resource allocation.

Treat your biodiversity data as a valuable asset. This means getting it organised, clean, and well-documented before it goes public.

- Create a data inventory: Catalogue all the biodiversity data your organisation holds, noting its source, format (e.g., spreadsheets, reports), and any known sensitivities.

- Standardise internally: Adopt a consistent internal data model based on community standards. Using a framework like Darwin Core (DwC) to structure your species data from the start will save significant effort later.

- Document with metadata: For each dataset, record the basics: what was measured, where, when, and how it was collected. This is essential to make your data Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable (FAIR).

- Handle sensitive data: If your data includes precise locations of endangered species, plan to obfuscate or generalise the location data (e.g., reducing coordinate precision) to prevent harm.

Outcome: Increased data reliability for internal sustainability metrics and external reporting

Legal clarity is non-negotiable. Addressing ownership and licensing upfront prevents future complications and builds trust with data users.

- Clarify ownership: Determine who legally owns the data. This is especially critical when it’s collected by third-party consultants, on private land, or from suppliers. Review contracts and get written permissions.

- Embed sharing in contracts: For future projects, include data-sharing clauses and co-ownership models in your contracts with partners and suppliers by default.

- Choose an open license: This provides legal certainty. Creative Commons (CC) licenses are the standard. Use CC-BY (requires attribution) or CC0 (public domain) for maximum reusability. If you have concerns about commercial reuse, CC-BY-NC (non-commercial) is an option, but be aware it can limit some scientific use.

Outcome: Mitigated legal and reputational risks linked to unclear ownership or consent.

Using common standards is the key to making your data interoperable and machine-readable, allowing it to be integrated into the global biodiversity knowledge base.

- For species data: Use Darwin Core (DwC). This is the global standard. You can package your data as a Darwin Core Archive (DwC-A)—a zip file containing your data (as CSVs) and metadata—which is the format expected by major platforms.

- For geospatial data: For habitat maps or environmental grids, use open formats like GeoTIFF or NetCDF. NetCDF is preferred for multidimensional data like that used for Essential Biodiversity Variables (EBVs).

- Use controlled vocabularies: Ensure consistency by using official species names from taxonomic registries, standard habitat codes (like EUNIS), and ISO country codes. This prevents ambiguity.

Outcome: Data is hosted where it can reach relevant audiences while maintaining the right balance of control and openness.

Publish your data where it will be discoverable and accessible to your target audience. There are several well-established options.

- GBIF (Global Biodiversity Information Facility): The world’s largest biodiversity data portal and the best starting point for most species occurrence data. Companies typically publish via a national node.

- OBIS (Ocean Biodiversity Information System): The equivalent of GBIF for marine and coastal data. The go-to platform if your operations are in marine environments.

- National & regional portals: Many EU countries have their own biodiversity data centres that feed into GBIF. Publishing through a national portal can offer more localised support.

- Trusted intermediaries: If direct publishing seems too complex, partner with a university, museum, or NGO that already publishes data. They can act as a data steward on your behalf.

Outcome: Your data becomes interoperable and machine-readable, multiplying its conservation and policy impact.

The publishing process is a key quality control step. Maintaining your data ensures its long-term value.

- Use platform tools: Use tools like GBIF’s Integrated Publishing Toolkit (IPT) to automate the process of uploading and mapping your data to the required standard.

- Validate your data: Run your dataset through the platform’s validator to check for formatting errors, missing coordinates, or invalid species names. Correct issues and re-upload.

- Plan for maintenance: If you conduct ongoing monitoring, establish a workflow for periodic data updates (e.g., annually). Clearly label dataset versions.

- Track your impact: Once published, your dataset will receive a persistent identifier (DOI). Use this to track how your data is being cited and used in research, which is a powerful metric for your own sustainability reporting.

Outcome: Minimised risk of error or misuse, and a clear audit trail for transparency, compliance, and continuous improvement.

Data sharing is not a one-off task but an ongoing practice. Building internal capacity and external partnerships is key to long-term success.

- Invest in skills: Provide training for your team on data standards and management, or hire expertise (e.g., a data specialist or ecologist).

- Automate where possible: Establish data pipelines to automate the export and formatting of data from your internal systems, reducing manual effort and errors.

- Foster a culture of stewardship: Make data sharing a recognised part of your company’s environmental policy. Assign clear roles and responsibilities for a ‘data custodian’.

- Collaborate to fill gaps: Partner with NGOs, universities, or industry peers. A mining company could fund local biologists for data collection and publication, while a food company could join a sector-wide initiative to standardise metrics.

Outcome: A sustainable, long-term data pipeline that evolves with regulatory, scientific, and stakeholder expectations.

The guide illustrates each step with practical examples and concrete recommendations. Whether you are just beginning to explore data sharing or looking to strengthen existing practices, it will help you turn biodiversity data into a strategic asset for both business and nature.

This guide is part of a broader set of Biodiversa+ reports on how biodiversity data are used and shared by businesses.